Jan 22, 2019

On January 1, 2019, the communist government of Vietnam, following China’s lead, put a new censorship law into effect. The law, passed back in June 2018, requires global technology firms with operations in Vietnam to keep user data there. Social media companies such as Facebook and Google, will be required to remove “offending content” from their services, within a day of receiving a request from the authorities.

The government of Vietnam claims that the purpose of the law is to provide cybersecurity for its citizens, but as critics have pointed out, it does little to provide cybersecurity and much to allow the government oppression of “free expression” for its citizens. Tech providers have protested loudly through the Asia Internet Coalition, a joint lobbying group, and they are considering to what extent they will comply. Google, for example, has faced great criticism in the west for agreeing to create a censored version of their search engine at the request of the Chinese government.

In China, internet censorship has gone even further. Following a couple days of rioting in 2009 in Xinjiang, northwest China, the Chinese government axed internet services overnight, cutting off access to 20 million people (population in 2009) in a region roughly the size of Iran. For some, the impact was devastating, as businesses dependent on the web, such as internet cafes, and travel agencies quickly went out of business. Some businesses had to send staff on a 1000 km (620 mile) journey to Gansu province, to get back online to communicate with customers and suppliers, manage university applications, or check in with families.

Consider how much more dependent many companies are now, a decade later. The internet runs call centers based on VoIP. It supports financial brokers, point-of-sale terminals, Cloud applications, team collaboration, and much more. Businesses perform credit checks, process loans, check product market values, and even perform security tests in order to verify identity.

Map showing the location of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Red Colored)

Map showing the location of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Red Colored)

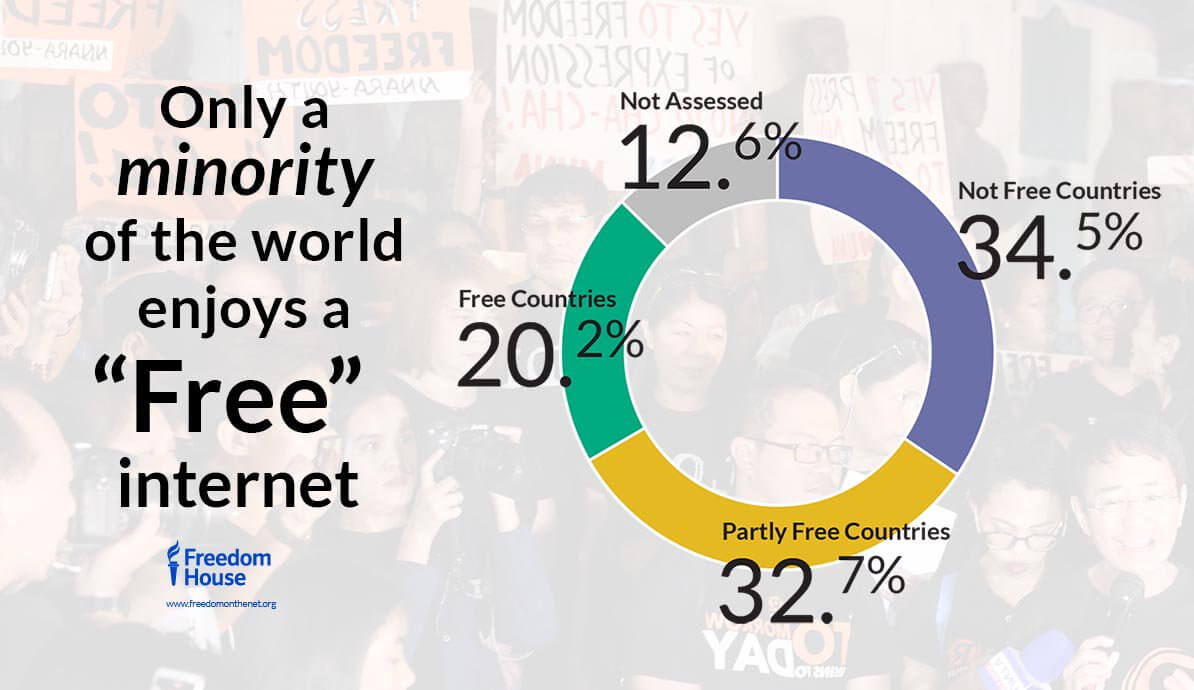

When the ban was lifted in China, websites focused on the Uyghur, an ethnic group, did not recover. Web admins were reportedly jailed, hardware seized, and the websites never came back online. Some suggest, such as Freedom House, a US NGO advocating for democracy, political freedom and human rights, that 2019 could be a banner year for protests and the use of censorship to squash or prevent them. China, renowned for its “Great Firewall,” has highly sophisticated, ingrained, top-down censorship solutions, primarily focused on information that originates from the rest of the world. Why is this year of special concern? There are a few reasons…

Every summer, upon the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, internet access in China becomes practically unusable. This is the 30-year anniversary of Tiananmen, when People’s Liberation Army troops, under orders from the country’s leader Deng Xiaoping, exercised a brutal crackdown on student and worker protests. 2019 will also see the 10th anniversary of the Urumqui riots in Xinjiang, mentioned above.

Source: Freedom House

Source: Freedom House

With its censorship capabilities, China has driven the Tiananmen protest movement into exile, with no good way to reach the young people needed to maintain and grow the movement. Many of the early leaders of the movement will be found in graves today. As always, activists will try to breach the firewalls, but the system is getting stronger every day. In China, June 4 is now known as “Internet Maintenance Day” given the many error messages encountered.

To throw a couple more sticks on the fire, it’s been 20 years since the Falon Gong spiritual movement was crushed. It is strictly forbidden to mention the group on the Chinese internet. It’s been 60 years since the Dalai Lama fled Tibet. On top of all that, a huge propaganda extravaganza is planned for Oct. 2019, celebrating the 70th birthday of the People’s Republic of China. The old Chinese curse, “May you live in interesting times,” may be exercised at length. Will the activists and protestors breach The Great Firewall? Will the Chinese censorship hold? With the ability to shut off the internet at will, as in Xinjiang, and numerous other locations, the Chinese government appears to be firmly in control.

Other countries are very interested. China is exporting its technology to other, mostly authoritarian countries, and providing training, technology and ideological support so that other countries can adopt similar internet systems. Some capabilities might be considered beneficial, such as blocking fake news sites, but the controls allow the government to stifle people and groups saying things the government doesn’t want them to say. Governments may censor for moral, religious, business, or political reasons, controlling “terrorist groups” as defined by the government, and perhaps referred to as “dissidents” by others. The governments who deploy these systems get the benefits of the internet for business and domestic communication, but they block or censor, that which they don’t want.

Source: Freedom House

Source: Freedom House

Who might be customers for the Chinese censorship technology? Some countries in Africa, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) might be interested. This country is leveraging a law passed in 2002 which governs the country’s telecommunications services and gives the government the ability to take control of communication facilities by invoking national security or public defense. Historically ISPs such as Bharti Airtel and Orange Group have complied, given that the government controls their licenses.

Internet penetration in the DRC is a little over 6%, but these 83 million people have been blocked, and throttled repeatedly in the past. Such a shutdown is in effect as of the writing of this article, as a result of protests based around the ongoing presidential elections. BusinessCom Networks learned of the current shut down when multiple in-country partners indicated that they needed to move between our VSAT sites in order to communicate, as the government had shut down the internet, at the points where it had control – namely the large ISPs. The DRC is currently struggling with the return of Ebola, and the outage has affected some, but not all organizations working to eliminate the virus.

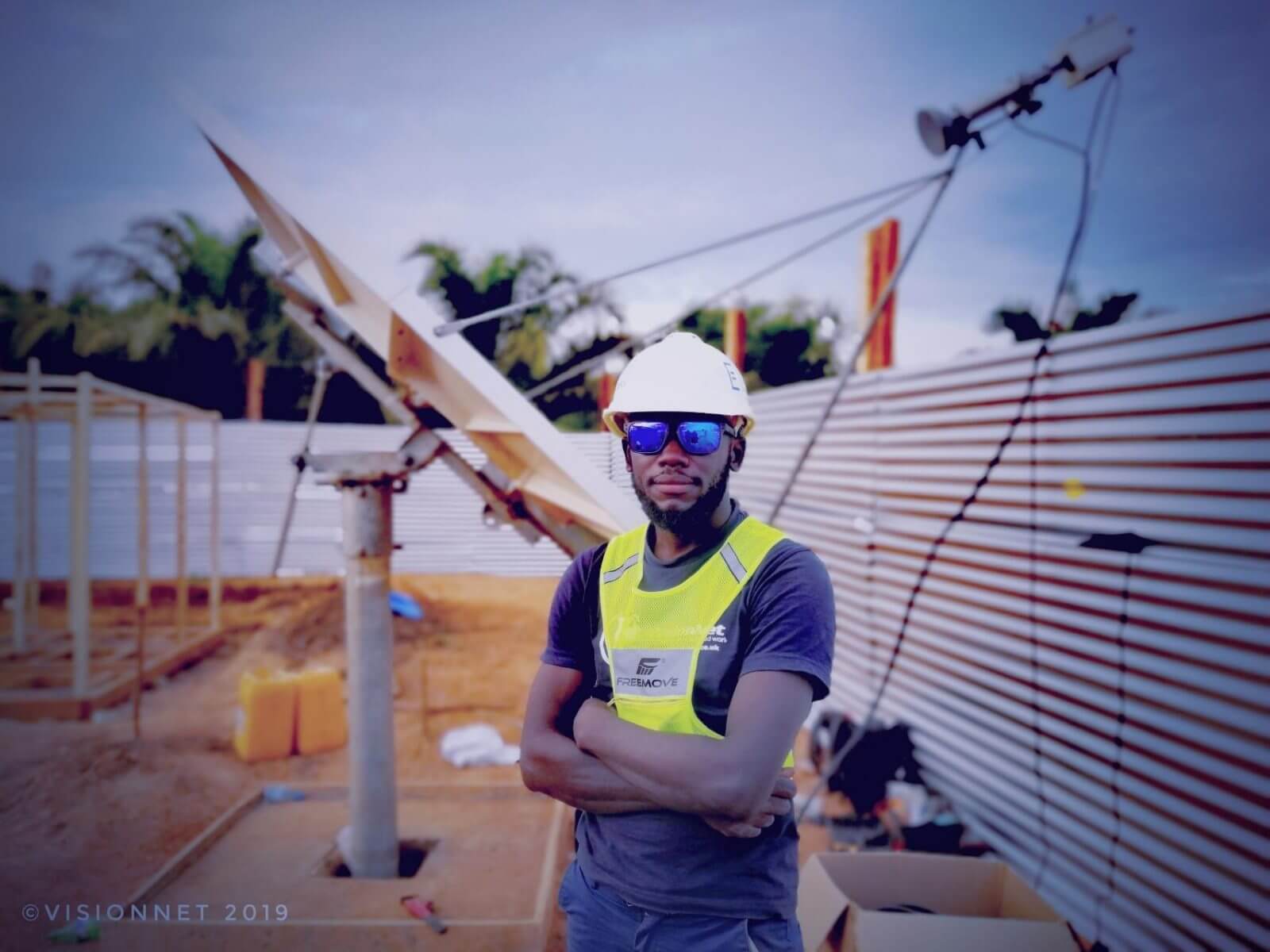

Alex Bahati

Alex Bahati

Alex Bahati, with BusinessCom partner VisionNet, recently noted: “After connecting (our customer) yesterday. I decided to take this moment to pose for the camera. It was not an easy activation, but we made it and 24 doctors can now call back home using Whatsapp, Skype etc. The joy was all ours to see the smile we bring on people’s face.”

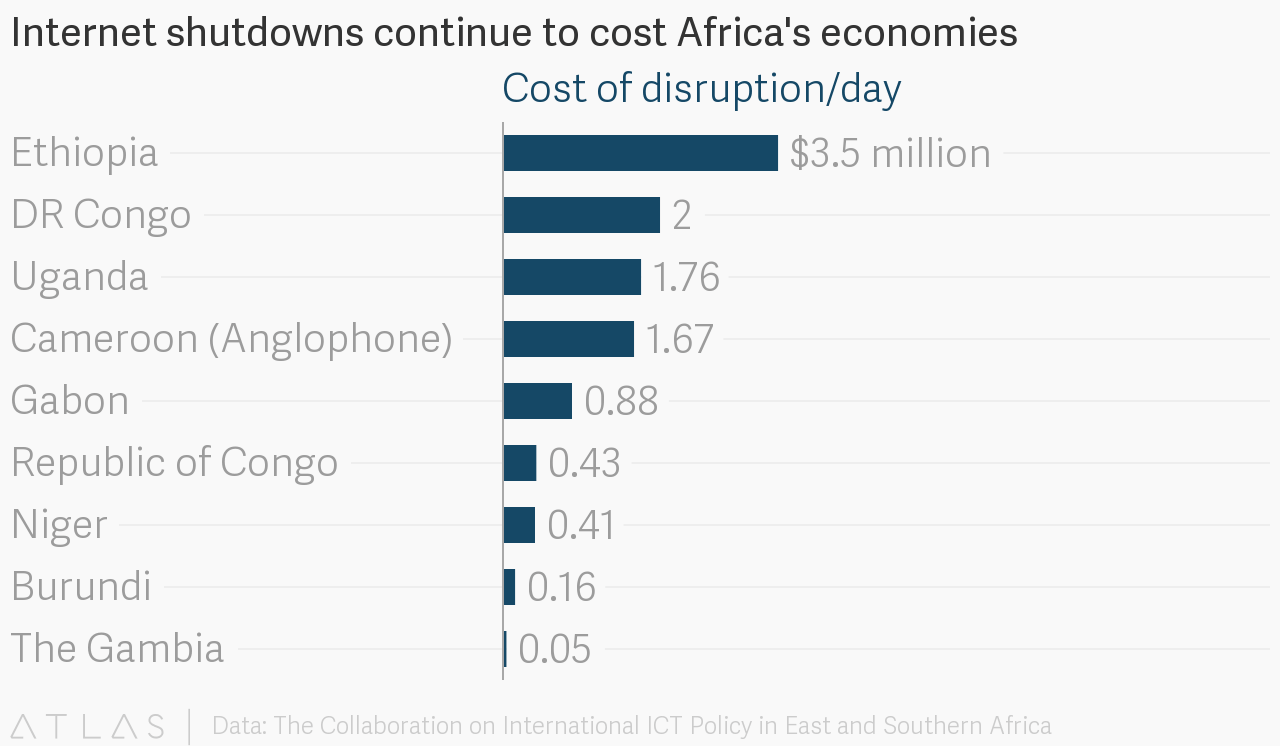

These shutdowns, while directed against activists and protestors come with costs. It can cost DRC on the order of $2 million USD per day when the entire internet is disrupted. The Chinese solution can target and block specific applications such as WhatsApp, Skype, Facebook and YouTube as a way of minimizing communications between protestors, yet allow banks, for example, to continue to operate. Whether some businesses may be allowed to continue to operate in DRC, is unknown, but it seems that currently, most or all internet users are affected as the country awaits the results of the highly-contested presidential election.

Is not just Africa. In December 2018, an Australian court gave a gag order that ran into the Information Age head on, when it attempted to keep news about the conviction of a very high-ranking Vatican official from reaching readers. Australian Cardinal Pell, 77, was convicted on five counts of child sexual abuse. The courts sometimes impose gag orders to shield defendants from negative publicity that could prejudice jurors in upcoming trials, such as Pell is facing.

The attempt failed. While Australian media was prevented from reporting the news, other organizations complied to a lesser degree, concerned primarily to the extent that any Australian operations could be subjected to penalties for contempt of court. Some organizations reported the news in print in their home countries, but the Australian effort proved futile, as Facebook and Twitter posts sent the news around the world in a flurry. Many of the posts included links to sites where the news was available. Will Australia express an interest in the Chinese model? What might the current president of the US do with such a capability?

BusinessCom Networks – because VSAT broadband satellite service is difficult to block!